A big focus on this blog has been centered around understanding and producing speech, but something that I have ignored up until this point is how speech is perceived. Speech perception is focused on hearing, decoding and interpreting speech. As we will see today, our brains are often not as reliable as we might think.

So rather than just turn this into a lecture about speech perception and the multitude of theories behind it (let’s face it, this is an educational blog, not a university course) I am just going to show off something weird and wild that our brains do and talk a little bit about the mechanics behind it. Alright, so raise your hand if you have heard of the McGurk effect. (Oh wait, sorry. Blog, not lecture)

The McGurk effect is an auditory illusion where certain speech sounds are miscategorized and misheard based on a conflict in what we are hearing versus what we are seeing. We can see this in action by watching the short video below.

So what is actually going on here? The audio that is being played in all three of those clips is exactly the same. You are hearing the same speaker say “ba ba” over and over. But when the audio is played over a video of someone mouthing “da da” or “va va” we are able to hear it as those instead.

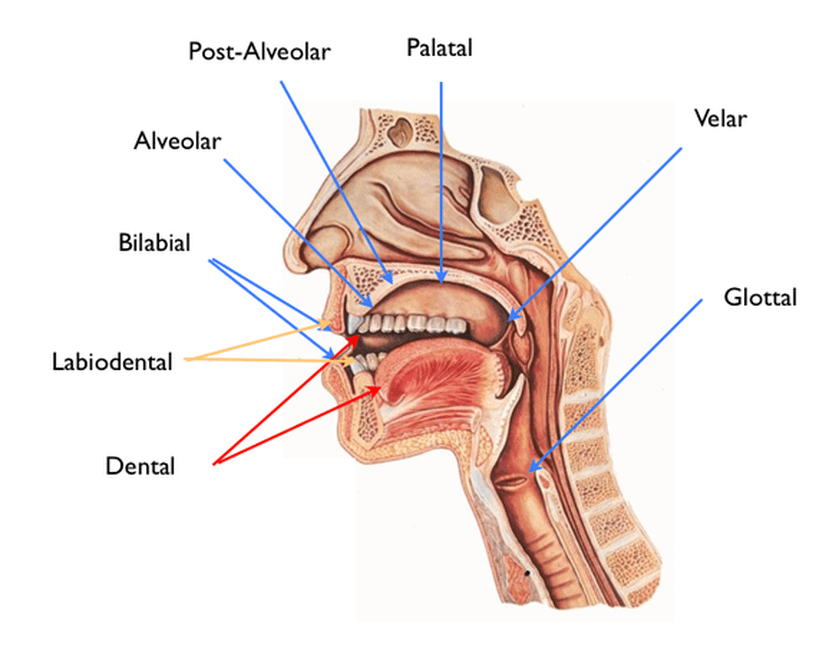

Well as it turns out, this illusion provides positive evidence for something called the motor theory of perception. This theory argues that people perceive speech by identifying how the sounds were articulated in the vocal tract as opposed to solely relying on the information that the sound contains.

This motor theory is supported by something like the McGurk effect because we are taking this audio information and supplementing it with what we are visually observing in the video in order to decide what is being said. It also explains why it is easier to hear someone in a crowded or noisy setting if you can look at their mouth and watch them speak as opposed to not being able to see their mouth.

But it’s not as though we are following along with what people are saying by moving our own articulators or imagining how their mouths are moving while we are listening to them. Supporters of the motor theory argue for the process with specialized cells in our brains known as mirror neurons.

A mirror neuron is a specialized neuron in the brain that activates (or fires if you prefer) in two different conditions, it will activate when the individual performs an action and it will also activate when an individual observes another performing the same action. In speech, this would mean the same part of your brain that activates when you move your mouth to produce a “ba” sound will also activate when you watch someone else produce a “ba” sound.

With this knowledge in mind, it should be easier to see why we are able to get something like the McGurk effect to occur. If perception of speech is influenced by visual information, and we are observing someone producing a sound that is activating these mirror neurons, it makes sense that our perceptions might change slightly so that what we are hearing matches what we are seeing.

It is important to note that, as I mentioned earlier, this is not the only theory of speech perception that we have right now, and the motor theory is not without its flaws. It relies on a persons ability to produce the sounds themselves. According to the motor theory, if you were unable to produce the sound yourself, and you could not visually see how the speaker was articulating the sound, you should not be able to perceive it.

So what about prelinguistic infants? An infant who has not developed the ability to speak yet should not be able to perceive the difference between a “ba” and a “da” without visual assistance because acoustically these sounds are quite similar.

Some studies have used a novel methodology where the infant will suck on a specialized soother of sorts that will measure the rate at which they are sucking. Using this soother and presenting the infants with audio stimuli through a speaker (no visual input), they have found that presenting infants with new and novel stimuli causes them to suck faster and presenting them with familiar stimuli means that they will suck at a slower rate.

So, by presenting these infants with a series of “ba ba ba” followed by a sudden change to “da da da” will result in an increased sucking rate. These findings are contradictory to the motor theory of speech perception because the infants in this study are too young to speak on their own and their articulators are not refined enough to be able to produce both a “ba” and “da” sound. Because the infants cannot produce these sounds at this point, their mirror neurons would not activate because they would not have developed fully yet.

This is not to say that the motor theory of perception is wrong though. The fact that we are able to perceive the McGurk effect means that their must be some truth to it. It just calls into question whether this theory captures the whole story. This is something that almost every science deals with at some point. There is almost never a perfect explanation or theory that deals with every problem. If you look hard enough, there will be counter evidence to almost any theory, but it becomes a matter of refining theories as we learn more and more about the way that the world works.

There are many other theories of speech perception that have their own explanations and their own problems. I will likely return to discuss some of the other big ones such as Exemplar theory, but for now I think this is a good place to leave this one.

Thank you for reading folks! I hope this was informative and interesting to you. Be sure to come back next week for more interesting linguistic insights. If you have any topics that you want to know more about, please reach out and I will do my best to write about them. In the meantime, remember to speak up and give linguists more data.