Have you ever thought about how you talk? I don’t just mean the way that you say certain words, or maybe the fact that you slur your words after a few too many drinks. I mean HOW you talk. The anatomy of the mouth and the way that your tongue does such quick and precise movements is truly fascinating. I also want to issue a pre-emptive apology because if you are anything like me, after reading this you will spend way too much time being aware your tongue. But enough of the preamble, let’s just get into it.

If you think about it for too long, tongues are just gross muscular things in our mouths. We use them when we eat to move food around in our mouths and to get food that was trapped between our teeth free, and of course they are primarily responsible for tasting. An often underappreciated function of tongues is their involvement in speech. This is not to say that tongues are essential for all speech, but they play a major part in the formation of both consonant and vowel sounds.

For reference, of the 23 English consonants in the International Phonetic Alphabet, only 7 of them do not directly involve the tongue. But this is just a little taste of what is to come. For now, lets talk about all of the things we need to classify a sound. When it comes to identifying a sound, there are three things we need to consider: voicing, place of articulation, and manner of articulation.

Voicing is not something that involves the tongue at all, but it is something that we have talked about previously. As a reminder, voiced sounds are produced with your vocal folds being held close together so they vibrate when air passes through them. You can feel this in a word like “zit” by placing your fingers on your neck as you say it. Compare this to a word like “sit” which has a voiceless sound at the beginning. Voiceless sounds are produced by keeping your vocal folds spread open so that there is no vibration.

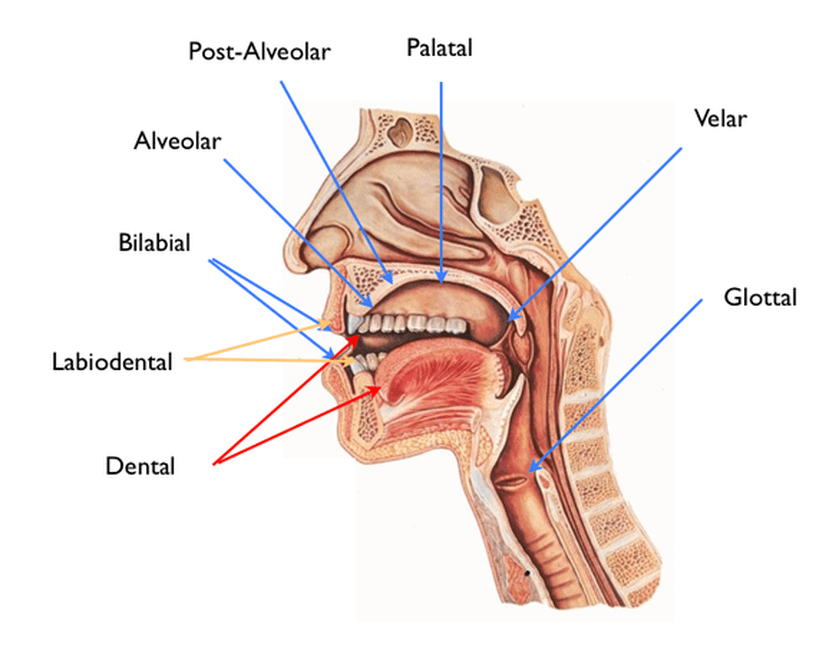

Moving up from the vocal folds, let’s get back to the tongue. We will begin talking about the tongue by discussing the different places of articulation. The places of articulation are mostly self explanatory with names like inter-dental (between the teeth) and bilabial (involving both lips), but the one we will discuss first deals with the “s” and “z” sounds we have discussed previously. These sounds are classified as alveolar sounds, meaning that they are articulated with the tongue at a place in your mouth known as the alveolar ridge. The alveolar ridge is just behind your upper front teeth and if you feel around with your tongue, you can feel a small protuberance where the roof of your mouth raises slightly. The diagram below shows a mid sagittal cross section of an oral cavity which shows the alveolar ridge, and all of the other places of articulation in the mouth.

Not all of these places involve the tongue as we previously discussed. All bilabial sounds like “b”, “p” and “m” are produced with only the lips and the tongue is not involved at all. Sounds like “f” and “v” combine two articulators (the teeth and the lips) to produce sound and these are known as labiodental sounds which, again do not use the tongue.

Before we move onto the manner of articulation, I want to talk about “r” for a second. “r” is a unique sound in English because it can be produced in two different ways depending on how you move your tongue. So now is when I ask you, are you a buncher or a curler?

To figure out whether you are a buncher or a curler, there is a simple test you can do. Go grab a toothpick or something similar that you are comfortable putting in your mouth and just poke your tongue as you are producing an “r” sound. If the thing you are poking is the bottom of your tongue, congratulations, that means you are a curler. If you are poking the top, then also congratulations, you are a buncher.

It turns out that an “r” sound can either be produced by curling your tongue tip back toward the rear of your mouth, or by just bunching up your tongue blade toward the back of the tongue. It is important for speech language pathologists to know about this so they can be prepared to teach techniques for both of them. There is no advantage or disadvantage to either technique, bunchers and curlers can both produce “r” sounds just fine. This is just a weird quirk of our bodies that we can observe.

Now back to the different sounds. Let’s talk about manner of articulation. Manner of articulation deals with the finer aspects of the tongue and how it directly impacts the airflow in the oral cavity. For example, lets return to the “s” and “z” alveolar sounds that we talked about earlier. These sounds are known as fricatives because they are produced by having the tongue very close to the place of articulation, but not touching it so that there is a small amount of space between them that results in a small amount of frication in the airflow, hence the name.

So now think about a sound like “t” or “d”. These sounds are both alveolar sounds as well, but they are produced by having the tongue touching the place of articulation and momentarily stopping the airflow entirely. Unsurprisingly, these are called stops. Now what about a sound like an “n” or an “m”. When you produce these sounds, you are producing them like you would a stop, but you can feel a little bit of reverberation in your sinus as you are producing them. These sounds are nasal stops, and they are produced by lowering the velum at the back of your oral cavity which allows the air to flow into your nasal cavity and resonate like that.

The amazing thing about all these actions is that they are not things that you actively need to think about to do. In fact, you probably put zero thought into how this works until you read this post. Our bodies can do all of this effortlessly and automatically.

As always, this is just a brief overview. We don’t have time to get into all the different places and manners of articulation. We will likely return to talk about more unique language sounds (like clicks), but for now, I think this is a good place to leave it.

Thank you for reading folks! I hope this was informative and interesting to you. Be sure to come back next week for more interesting linguistic insights. If you have any topics that you want to know more about, please reach out and I will do my best to write about them. In the meantime, remember to speak up and give linguists more data.