Whether its to express anguish or to emphasize something excitedly, The F Word is a versatile word within the English language. We all know that it can be a noun, a verb, and an adjective already, but a lesser discussed feature of it is what It can do inside of a word. The ability to insert The F Word into the middle of a word, or infix it, is constrained by the underlying structure of the word.

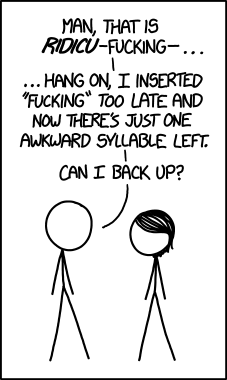

Take the word “fantastic” for example. It’s a three-syllable word with no prefixes of suffixes. We can easily insert The F Word after the first syllable and end up with something like “fan-fkn-tastic”, but we can’t put it between the second and third syllables to make something like “fanta-fkn-stic” (or fantas-fkn-tic depending on how you want to divide it).

You can probably think of some other three syllable words that pattern the same way so you might try to generalize that The F Word can be inserted between the first and second syllable of a word. But what about a four-syllable word like absolutely. You can “abso-fkn-lutely” break it up like this, but it’s “ab-fkn-solutely” weird to put it anywhere else.

So what can this tell us about the structure of these words then? If it’s not just about the syllables, what is constraining where we put The F Word? This is where we need to talk about the concept of a prosodic foot. This is a concept that you may already be familiar with if you study poetry.

Essentially, a prosodic foot within a word is what gives us a sense of rhythm within a word. Prosodic feet are composed of two (disyllabic) or more syllables in a word, one of which is stressed or “long”, and the rest being unstressed or “short” (there are cases of all stressed syllables and all unstressed syllables in a foot, but we won’t be talking about those today). The two most common types of disyllabic feet that you have likely heard of are iambic feet and trochaic feet. In an Iambic foot, the second syllable will be stressed while in trochaic feet, the first syllable will be stressed. Iambic feet are pretty well known thanks in part to William Shakespeare and his penchant for writing in an iambic rhythm.

With these definitions in mind, lets review some of the words from above:

If we assign a beat structure of sorts to these words where “DUM” is a stressed syllable and “da” is an unstressed syllable we can see that they both have uniquely different rhythms.

Fantastic – da-(DUM-da)

Absolutely – (DUM-da)-(DUM-da)

The two words shown here both happen to have trochaic feet where the first syllable in the foot is the one that is stressed. So now we can adapt our rule to say that the F word can only be infixed in front of a foot.

Of course, this just wouldn’t be English if there weren’t a few exceptions to the rule. What about a more complex words like “unbelievable”? I think we can all agree that “un-fkn-believable” sounds a lot better than “unbe-fkn-lievable”. Linguists have adapted the rule to prioritize morphological boundaries of a word over the rhythm and foot structure in these cases, and because the “un” in this word is a prefix that attaches to the word “believable”, we would prefer to separate it for the sake of infixing than to use the rhythm structure and leave behind this “unbe” thing.

Now think about a word like Kalamazoo. You might be okay with both “Kala-fkn-mazoo” and “Kalama-fkn-zoo”. Maybe you have a strong preference one way or the other. At the end of the day, there is no perfect answer to the problem of where we can infix The F Word in English, but there are certainly some interesting things you can do with it. I encourage you all to go out there and see what you can F up!

Thank you for reading folks! I hope this was informative and interesting to you. Be sure to come back next week for more interesting linguistic insights. If you have any topics that you want to know more about, please reach out and I will do my best to write about them. In the meantime, remember to speak up and give linguists more data.