Historical linguistics is an incredibly fascinating subfield of linguistics with so many areas to explore. Rather than focussing on the language that we have now, historical linguists spend their days looking through old documents to try and understand how language and evolved over long periods of time.

It turns out there are so many consistent changes that have happened over time and doing this type of analysis has taught us so much about the universal rules of language change. We are going to talk about one peculiar case of language change though that was brought about by a strange superstitious belief. Let’s talk about the English word “bear”.

Before we talk about “bear”, let’s introduce some historical knowledge and general knowledge about language families. As you may already know, all of the languages in the world can be divided into groupings of languages called families that are related to each other in some way and share a common ancestor like a family tree of sorts. Two of the most well known language families that we will be focussing on today are languages in the Romance family (Spanish, Italian, French) and languages in the Germanic family (German, Dutch, English). There are many more language families out there that are all doing their own unique things, but these are the two that we will talk about for today.

First, let’s dive into Romance languages. Romance languages are all directly descended from Vulgar Latin and as a result of this close common ancestor, they share much of their vocabulary and grammatical rules. There are of course large distinctions in pronunciation and such that have developed over time, but you have likely noticed in your own life that a lot of the words in a language like French are quite similar to Spanish and Italian.

So let’s bring it back around to “bear”. “Bear” is no exception to the above facts. The French word for “bear” ours/ourse is similar to the Spanish orso which is similar to the Italian orso/orsa. These are all so similar because they would have derived from the Latin word ursa, which is likely not a huge surprise when you think about the name of the constellation “ursa major”, which was named using the Latin word for bear.

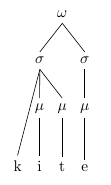

This is all very cool and interesting, but we need to remember at this stage that Latin was not the first language on earth. It’s not like Latin just showed up and created the word ursa for bear and things evolved over time. If we back it up even further, we arrive at a language that is known as Proto-Indo-European. Proto-Indo-European (or PIE for short) is a theorized language that existed from around 4500 BC to 2500 BC. I say theorized because, at this point at least, there are little to know written records that prove the existence of PIE. The reason we believe PIE exists is because there are many examples of languages in Eastern Europe and Western Asia that have common words and patterns in their language, and they can all be traced back to this hypothetical ancestor in some way or another.

A quick example of this can be shown by looking at some Italian and English comparisons. For instance: piede and foot, padre and father, pesce and fish… there are so many words in just these two languages that have developed to different forms over time, but their patterns are very consistent. The ”p” sounds in Italian seem to be roughly parallel to “f” sounds in English in all of these words for instance. Now I know this is just three words in two languages but trust me when I say that there are hundreds of examples across dozens of languages that give extra weight to this theory.

So if we trace the Latin word “bear” back to PIE, we end up with something like this: *h₂ŕ̥tḱos (note here that the asterisk is to mark the fact that this is a hypothetical reconstruction based on comparing many many languages. Like I said, we don’t actually have writings that include this word).

Where this starts to get really interesting is the fact that this PIE word can trace down to other languages in the PIE family that are not romance languages. Let’s look at the Greek word for “bear” now.

In Greek, the word bear is άρκτος (pronounced “arktos”) and you can notice two things from this. First off, the word arctic in English is derived from this in some way, which is how we have something like the Arctic Ocean, because this is the ocean that is in the northern direction where the Ursa Major constellation is (it’s all tying together again!). The second thing that you can notice is that “arktos” looks roughly like how the PIE word for “bear” would be pronounced. This is giving us more evidence that maybe PIE is a real thing and that all of these languages are tied together!

Now those of you with keen perceptions may have noticed something that I did when I first introduced PIE. I used evidence of English and Italian words to convince you that PIE was real. But if PIE is real, and we can trace back words to this common ancestor… how the heck did we end up with bear instead of something more closely related to *h₂ŕ̥tḱos?

It turns out that it’s not just English that has this “bear” problem either. This is where we start to talk about the Germanic lineage. Germanic is also descended from PIE, but not from Latin (English has a lot of Latin influence, but let’s thank the Norman invasions for that). The family tree in this instance splits off directly from PIE and gives us two subfamilies; one with Latin that bears (no pun intended) Romance and Mediterranean languages, and the other side with the Proto-Germanic languages. There are many other divisions and such, but we are only going to talk about these two for now.

All of the Germanic languages have similar words for “bear”. German has bär, Dutch has beer and many Slavic languages (also descended from Proto-Germanic) have it too (Swedish björn and Norwegian bjørn for instance). So with this evidence, it is clear that something happened to the Proto-Germanic word for “bear” that caused this shift.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the Romance languages and see what words that they do have which are similar to “bear” and it might give us a clue.

French has the word brun meaning brown, which was derived from the Latin word brunius. While these may not appear to be exactly the same as “bear” on the surface, it turns out when we trace back the word “bear” in the Germanic and Slavic families that they are in fact derived from the word “brown” somehow.

So what happened to the Proto-Germanic people to make them start referring to “bears” as “the brown ones”. Historical linguists theorize that the Proto-Germanic people were very superstitious people, and because of their superstitions, they were worried that calling a “bear” by its true name would bring it into your life somehow and increase the likelihood of “bear” attacks in ones life.

By a process known as euphemism, it is thought that the Proto-Germanic people collectively started to refer to *h₂ŕ̥tḱos as “the brown one” simply because they needed a way to talk about them without risking summoning them to their camps or hunting excursions.

The Proto-Germanic people had their own version of “he-who-should-not-be-named”, but instead of being some literary euphemism, it ended up influencing thousands of years of language use and giving me something to write about! This is the sort of stuff about language that I find truly fascinating. The fact that we can take this weird thing that you have likely never given a second of thought to and develop entire theories and papers and blog posts to talk about it in an informed and educated way.

So the moral of the story is: keep your friends close and your *h₂ŕ̥tḱos far away by calling them bears instead!

Thank you for reading folks! I hope this was informative and interesting to you. Be sure to come back next week for more interesting linguistic insights. If you have any topics that you want to know more about, please reach out and I will do my best to write about them. In the meantime, remember to speak up and give linguists more data.